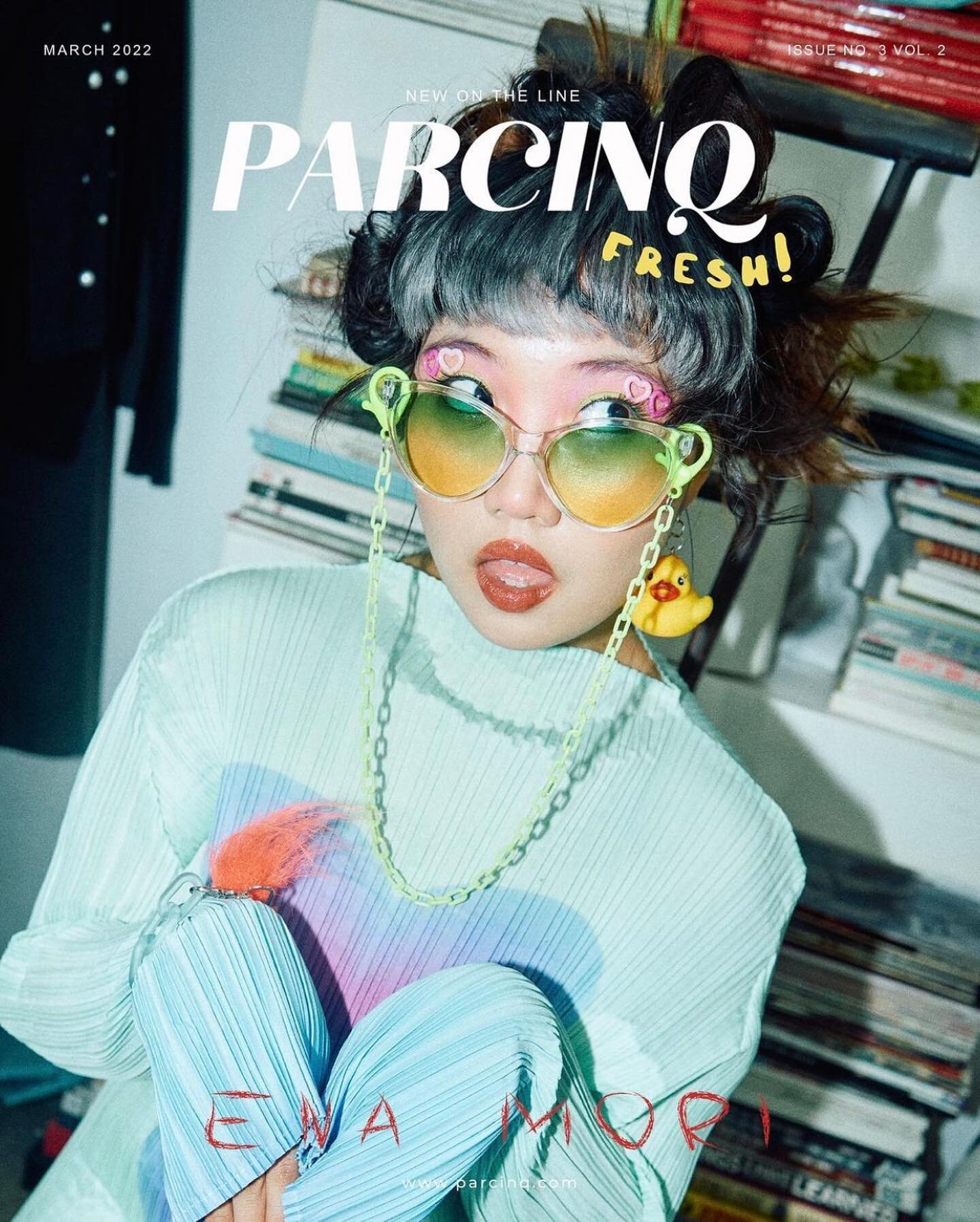

A Behind-the-Scenes Look at Witness To A Devouring Monster

Lei Nico in Awakener. Photo: Meghan Farrell

In 1936, the French-Cuban writer Anaïs Nin wrote in her diary, “The monster I kill every day is the monster of realism,” and that “Introspection is a devouring monster.” These words have particular resonance for writer and actor Lei Nico. As a woman of Asian descent in America, she has had to wrestle with the paradoxical reality of being at once invisible and at the same time continually subject to another’s (often a white cis male’s) gaze; of being disposable yet essential in service to others. We were brutally reminded of this reality by last March’s fatal shootings of six Asian women at spas in Georgia by a white Christian man who blamed his victims for his sex addiction and justified their killings as eliminating “temptation.”

The fetishization and dehumanization of Asian women is deeply rooted in Western psyche and culture (Nin herself, as a product of her time, perpetuated it by reappropriating the “Oriental” for her own sexual liberation). For good or ill, our introspection as Asian American women and our decolonization as Pinays often begins by confronting our own objectification. In Nico’s case, introspection conjured her debut anthology film, Witness to a Devouring Monster, where she voices the stories of three Filipinxs from different worlds — Ana, Xenia, and Magan — who come out of their silences to meet their monsters.

Photo: Meghan Farrell

The first film, Awakener, is set in 1902 in the Philippines, ceded after three centuries by Spanish colonialists to the Americans in an ongoing mission to spread the twin gospels of Christianity and white supremacy to the “heathen” islanders. Our eye immediately is caught by Ana, who enters the scene attired in a traje de mestiza — known colloquially to Filipinos as a Maria Clara gown and named after José Rizal’s mestiza heroine in Noli Me Tángere, who embodies the Filipino author’s Western ideal of womanhood and reveals his own contempt for Asian women whom he finds “are ignorant, are slaves.”

In her research, the film’s costume designer Victoria Garcia notes that the Maria Clara, much like its namesake, “is specific to the times, where it was heavily influenced by Western cultures but still was very much Filipino,” for instance in its use of indigenous materials such as piña or jusi cloth. Ana alludes to the Filipinos’ creative manipulation of language as well, name-checking multilingual intellectuals and revolutionaries in her monologue, “Plaridel has not penetrated you. You cannot read Mabini. But I speak your language …” Ana, wed to a foreign soldier (the “you” she refers to in her speech), outwardly conforms to the mores and customs of her colonizers, but her words reveal an awareness of a pre-colonial self and a hybrid self that she can weaponize against them.

Photo: Meghan Farrell

We then are introduced to Xenia in the film Two Women. The opening underwater scene was the most challenging to shoot. Director of photography Geetika Kumar and the crew had to create a black box in an aquatic center pool and set up the lighting and shots 15 feet below the surface of the water. On the surface, Xenia is all smiles and seductions. But inside she is drowning, “desperate and bewildered” by a world that is blind to her multidimensionality as a human being and that chooses to see her only as a woman subservient to the sexual fantasies of often powerful, violent men.

Photo: Meghan Farrell

Xenia’s story demanded introspection and vulnerability and was personally difficult for Nico to write. “It made me anxious writing about an Asian woman who chooses to utilize her sex appeal in order to survive,” she said. “I wondered if an American viewer could recognize her trauma and sympathize with her, or if they would keep seeing Asian women as objects of desire, continuing to threaten our safety and mental health.” Nico had her doubts — especially after the Atlanta shootings — but ultimately chose to voice that collective pain and trauma from violence that many of us suffer, instead of being silenced or having the narrative taken away from us and misrepresented in the dominant culture.

The third film, Magindara, is about Magan’s transformation from assault victim to a survivor who, by re-membering and telling her story, regains more than just her corporeal self at the end of the film. According to Filipino (specifically Bikolano) mythology, the magindara are half-human, half-fish creatures who were guardian spirits of the sea or alternatively, spirits who lured fishermen to their deaths with their voices. Their voices could summon rain to nourish the land as well as storms and floods to destroy it. At the end of the film, we see Magan sitting in a shroud of fog — she is of the storm. Magan uses her voice not to destroy, but to empower us to wield the wisdom of the universe contained within ourselves.

Photo: Meghan Farrell

Weaving in Filipino folklore and mythology, Magindara also serves as a bookend to Awakener — reminding us that the systemic annihilation of our matriarchal, gender-fluid society is one of the most damaging legacies of colonialism. Since precolonial times, the babaylan (also known as katalonan or mumbaki, who most often are women, trans, intersex, or gender-fluid people) have occupied a prominent role in society as augers of fate, healers, midwives, and mediums who can commune with the dead. So threatening were the babaylan to the misogynistic Spanish colonists that their bodies were chopped up and fed to the crocodiles. One might even trace modern-day femicides and the killings of trans women (the Philippines has the second worst record in Asia for murdering trans people, next to India, a country with 11 times its population) to this colonial practice.

While the film initially was inspired by Nin’s writings — lyrical explorations of one woman’s sexual fantasies as well as a risky dare in her time to be as open about sex as the male writers she was surrounded by — Witness to a Devouring Monster refracts the lens to center the experiences and the internal lives of brown women. The entire production embodies and represents the diversity and multidimensionality of Pinxy and other brown women’s experiences. As Nico puts it, “This film is part of a larger movement of creators who actively carve out space for themselves and their communities, creating possibilities beyond the monolithic expectations of brown people by the entertainment and film industries.”

Behind-the-scenes of Awakener. Photo: Meghan Farrell

There still are post-production and distribution challenges to overcome in order for the film to be made publicly available and for its vision to be fully realized and shared with the community. Producer Roxanne Lim shined a light on some of the difficulties of producing independent films by marginalized creators, particularly how the project has been directly impacted by implicit biases that are perpetuated in entertainment.

“The speed at which certain male-led and male-scripted films have gotten funded even during a time like COVID is impressive,” she said. “To be quite frank, even with tons of visibility, we have yet to come close to our goal. As a producer it makes me curious as to what the reservations about a brown woman-led production really are — is it truly hard to imagine a world where a narrative such as Witness is supported with as much normalcy and eagerness? Is it wrong for us to desire our own fantasies, to be the subject with potential to relate, instead of simply being the object made for consumption?”

These challenges have further galvanized Lim and the team to see Witness through to completion. It is more than just getting this particular film funded, but rather demonstrating through community support that there is value in backing art that deviates from the “norm” only in that it demands centering brown women creators in representing and imagining greater possibilities for ourselves.

To learn more about the film and the team behind it as well as to support the efforts to fulfill deferred payments to the cast and crew, finish editing the film, and get it out to festivals and to the community, check out their Seed & Spark campaign (and the great incentives, including a virtual storybook, screen credits, private screenings, and more), running through May 21.

Vina Orden

IG/Twitter: @hyffeinated

Vina Orden (she/her/siya) is a writer, artist, and immigrants’ rights and social justice advocate based on Lenape land/New York City. Currently, she is a nonfiction contributor to The Margins digital magazine of the Asian American Writers' Workshop and Associate Editor for poetry and creative nonfiction at Slant’d magazine. She also is the co-host, along with Tamara Crawford, of The Lift Up, a monthly transatlantic conversation about books, writing, identity, and representation. She was a writer and cast member of the award-winning 2019 production of “Raised Pinay” and a member of the We Make America artist/activist collective.