Dear Non-Black Filipinx Fam: We Need to Stop Saying the N-Word

Illustration by Eduardo Daza Taylor IV for Hella Pinay

In college, people in my circle — most of them Filipinx and other Asian Americans — sometimes referred to each other by the N-word. I didn’t join in. Since I rarely heard it growing up in white suburbia, saying it would feel clumsy and fake — and since I wasn’t Black, it wouldn’t feel 100% okay, either. Too terrified of conflict to speak up, I tried to rationalize the situation. They mean it like “homie,” I thought. Some of them grew up around Black people, who probably said it all the time. It’s not as bad as if they were white.

Looking back, I should’ve said something. I was wrong — we were wrong. Now, I have the context and vocabulary I didn’t have at the time to articulate why.

More than half a year since the murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and other Black Americans at the hands of police mobilized people around the world against white supremacy, major media outlets have published stories about Black and Asian solidarity, the history of anti-Blackness in Asian communities, and the need to talk about anti-Blackness with our Asian immigrant family members. But I have yet to encounter one about the use of the N-word among Asian Americans, let alone Filipinx Americans. It's definitely A Thing — chances are pretty good that if you’re Filipinx, you know another Filipinx who’s used this word, or you’ve used it yourself. Other non-Black communities of color grapple with the same issue.

The Filipinx Americans I interviewed trace the use of the N-word in our community to a multitude of origins, including our frequent proximity to Black Americans, our struggle to find our identities in a society that has largely erased us, and our own racial trauma. While these factors illuminate why some of us use a word that was, and still is, invoked to dehumanize and kill Black people, they don’t justify it. Black people can reclaim the N-word if they choose to — but it was never ours to begin with. Non-Black Filipinxs have no business saying it.

For some of us, using the N-word might reflect a search for where we belong in a country that defines race in the narrowest of terms. “I feel like, in the U.S, there’s such a binary of how we understand race,” says Rohan Zhou-Lee, an organizer and founder of the Blasian March, who’s Black, Filipinx, and Chinese American. “Everything is always Black and white. There’s always the question of, where does the Asian American, or in this case, where does the Filipinx American fit into that story?”

Our community has inherited trauma dating back to Spain and the United States’ occupations of the Philippines — American soldiers called Filipinxs the N-word during the Philippine-American War — and more recently, during the Manong/Manang era, when white people exploited Filipinx Americans’ labor, and even lynched them, a story still largely left out of history books. “Because of that untold history of violence, it’s easy to latch onto a very widely publicized narrative of violence, which is the Black experience,” Zhou-Lee says.

That said, even though there are parallels between the Black and Filipinx experiences, they’re not the same. Zhou-Lee wonders if Filipinxs’ use of the N-word stems from a warped sense of empathy for Black struggles. Whether you’re using it in a loving or hateful way, “in the end, your trauma is never an excuse to perpetuate more trauma.” Also, the use of the N-word against the Manongs/Manangs was still rooted in the dehumanization of Black Americans and enslaved Africans. “You still have to acknowledge the root usage of that word.”

E.J.R. David, a professor of psychology at the University of Alaska Anchorage, also believes that citing this historical parallel as a rationalization for using the N-word today is flawed. “The scale and intensity with which the N-word was used to damage and hurt Black people across generations —including today, by the way — is so different from how the N-word was used against Filipinos,” he says. “There might have been a time in our history when white folks treated us like they treated Black folks, but we are not Black.” The N-word is no longer used to hurt and kill us the way it’s still used to hurt and kill Black Americans.

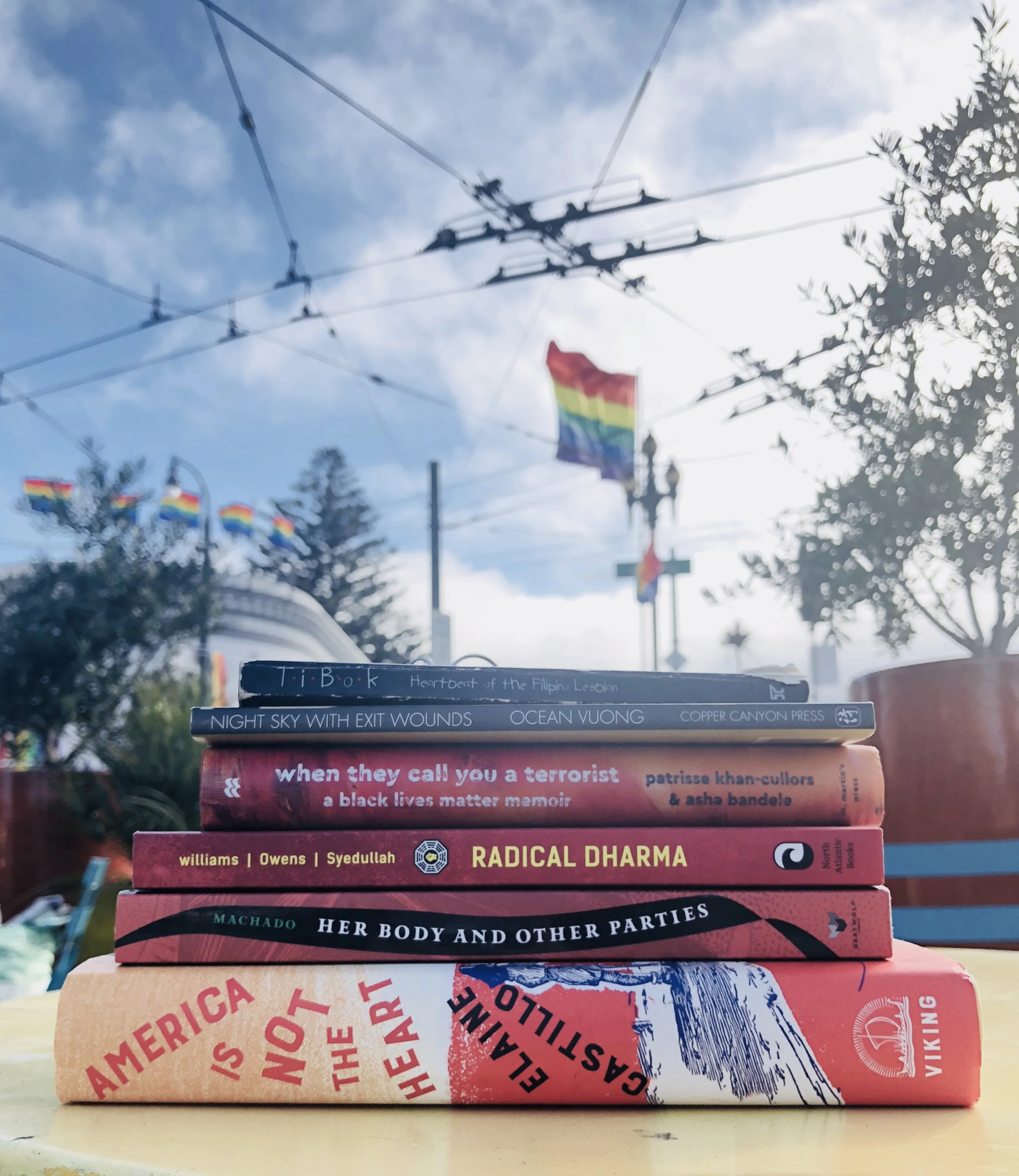

Rapper and journalist Rocky Rivera dropped the N-word from her vocabulary years ago, having reached a similar realization. She describes the truths she learned to accept in the essay entitled “Just A Word?” from her forthcoming book, Snakeskin, which she shared with Hella Pinay. “No amount of ‘passes’ or cultural-context flips by Tupac could excuse me from perpetuating a harm that Filipinos did not collectively experience in America, back then through slavery & Jim Crow, or currently, through the discriminatory justice system and racial profiling,” she writes. “It might have been used against Filipinos during the wars and imperialistic quests to conquer the Philippines, but it did not originate from our experiences in America.”

None of this is to minimize the racism we experience today. But we know for a fact that racism most heavily impacts Black folx, David points out, “and the use of the N-word is part of that system of dehumanizing Black people and keeping them at the bottom of this white supremacist racial hierarchy.” Using it, even out of a misguided sense of camaraderie, normalizes it and makes us complicit in this system. “Empathizing and relating to the pain Black people have experienced is different from appropriating it.”

Colonial mentality — which might’ve, say, dissuaded our parents from teaching us Tagalog or connecting us to our culture in other ways — could help explain this appropriation of Black culture and the N-word. “For a lot of us who don’t have a relationship with the Philippines, and America is all we know… we don’t have a visibility and representation here. We don’t have an understanding of where we come from,” rapper Ruby Ibarra says. To fill this void, we might identify ourselves through the pop culture we consume — and because so much of pop culture takes from Black culture, it makes sense that some of us would identify with it.

Our environments shape our language, too. Some Filipinx Americans use the N-word because they heard it all the time where they lived. “It comes as no surprise to me that I heard the N-word growing up just because of the racial makeup of the spaces that I was in,” says Ibarra, who was raised in Hayward, a highly diverse city in the San Francisco Bay Area. Half of the students in her elementary school were Black, while the rest were mostly Latinx and Asian. And in the Bay, she adds, "hip hop is such a heavy part of the culture. I think that also influenced a lot of the language that people chose to use.”

That said, Ibarra doesn’t believe these factors excuse the N-word. From an early age, she understood it wasn’t hers to say, as someone who wasn’t Black or from the U.S., so she’s never used it herself. After taking ethnic studies in college and learning more about the ugly history of the N-word, she realized she should’ve spoken up when she heard her non-Black classmates use it years ago. “I think oftentimes when you’re a kid, it’s difficult to interrogate what is normalized around us and accept it as part of the culture.”

Ibarra believes that the use of the N-word among Filipinxs — including casually, without interrogating why it’s harmful — boils down to the anti-Blackness that pervades our community. Those of us in hip hop spaces in particular need to remember that this is not our art form, she says. “This is just something we’re borrowing from Black community, something that they created.”

When non-Black people of color say the N-word, it perpetuates a sense of trying to take ownership of Black culture, Ibarra adds. Zhou-Lee agrees. “This isn’t the trauma you’ve inherited, so you don’t really have ownership over it,” they say. Even if you grew up in a Black neighborhood and know the culture well, you’re still not Black. “One way to appreciate that culture best is to understand your limitations in that culture, as a guest to that culture.”

While some of us might feel like we get a pass because our Black friends are cool with us saying the N-word, Ibarra urges us to consider the bigger picture. Amid continued police brutality against Black Americans, we need to do better than “My homie says it’s ok,” and think critically about anti-Blackness in this country. Also, your Black friends don’t speak for all Black people. Some, like Zhou-Lee, choose not to use the N-word. Zhou-Lee doesn't want others to call them by it, either, which they owe not only to their inherited trauma, but the direct trauma of white people calling them the N-word as a hateful slur.

Creating a dialogue around where the use of the N-word in our community comes from can help us understand that we can’t use it to channel or navigate our trauma, Zhou-Lee says. It can also allow us to craft our own narrative rather than appropriating others’. But our tendency to stay silent about difficult subjects due to a belief, rooted in colonial mentality, that we need to put our heads down and not cause an uproar, can discourage such conversations, Ibarra says.

Potential case in point: When I put out a call for Filipinxs who’ve used the N-word on Facebook and Twitter for this story, I received zero responses. (And believe me, there’s no shortage of Filipinxs among my friends and followers.) Even after others boosted my posts, even after I broadened my query to include Filipinxs who knew other Filipinxs who’ve said it — crickets. The silence makes sense, though. The use of the N-word in our community is like an open secret. We know Filipinxs say it, but maybe we’re ashamed that they do, so we hesitate to acknowledge it.

So how do you start a dialogue with a Filipinx who uses the N-word? First, it’s imperative to acknowledge and name it when they do say it, artist/organizer DJ Kuttin Kandi tells Hella Pinay. At the same time, slow down and explore your POP: the purpose of your conversation, the outcome you want, and your process for enacting change. Know that tension can surface if you drop social justice terms based only on what you’ve read about anti-Blackness to someone who has lived experience with it. They may not be able to articulate it in the same verbiage as you, but “they know what anti-Blackness looks like because they see their friends policed every day.” Recognize your own anti-Blackness, rather than swooping in as a savior.

Think in terms of relationships. “If my goal was to just call them out and have no relationship, what is that going to do?” says DJ Kuttin Kandi. “Is that person going to change?” If you truly want to uproot anti-Blackness, you need to also build a path forward to help them undo years of conditioning in a white supremacist society. “That’s the real work. The real work is not just calling someone out.” That requires building trust, which takes time. Meanwhile, the other person needs to have “the openness to decenter themselves, the willingness to do the work. If they don’t have that, then of course the repair cannot happen… It has to be a mutual thing.”

David agrees that if you really want to reach that person, you don’t want to enter the conversation accusing them of harboring racist or anti-Black sentiment. “My advice would be to talk to them about how hurtful that word is, and how that word continues to literally kill Black people today,” he says. Maybe suggest replacing the N-word with something like “fam,” or “sibling,” or better yet, terms of endearment in our own languages, like Ate, Kuya, Manang, or Manong.

“There’s a lot of different languages in the Philippines that we can draw from that convey the same message of connection and empathy and care and love and being able to relate,” he says. “To me, that would be more powerful than using the N-word.”

We can show solidarity without traumatizing, without upholding anti-Blackness, without appropriating Black culture. We can imagine an alternative that empowers all of us. But to do that, we can’t swallow our discomfort, like I did years ago, like so many of us still do. We need to break our silence first.

Melissa Pandika

INSTAGRAM - WEBSITE

Melissa Pandika (she/her) writes about wellness, race, and identity. Her words have appeared in The Cut, VICE, Mic, and many other places. She lives in the Bay Area and is at work on a memoir.