Brown Asians are Asian, Too

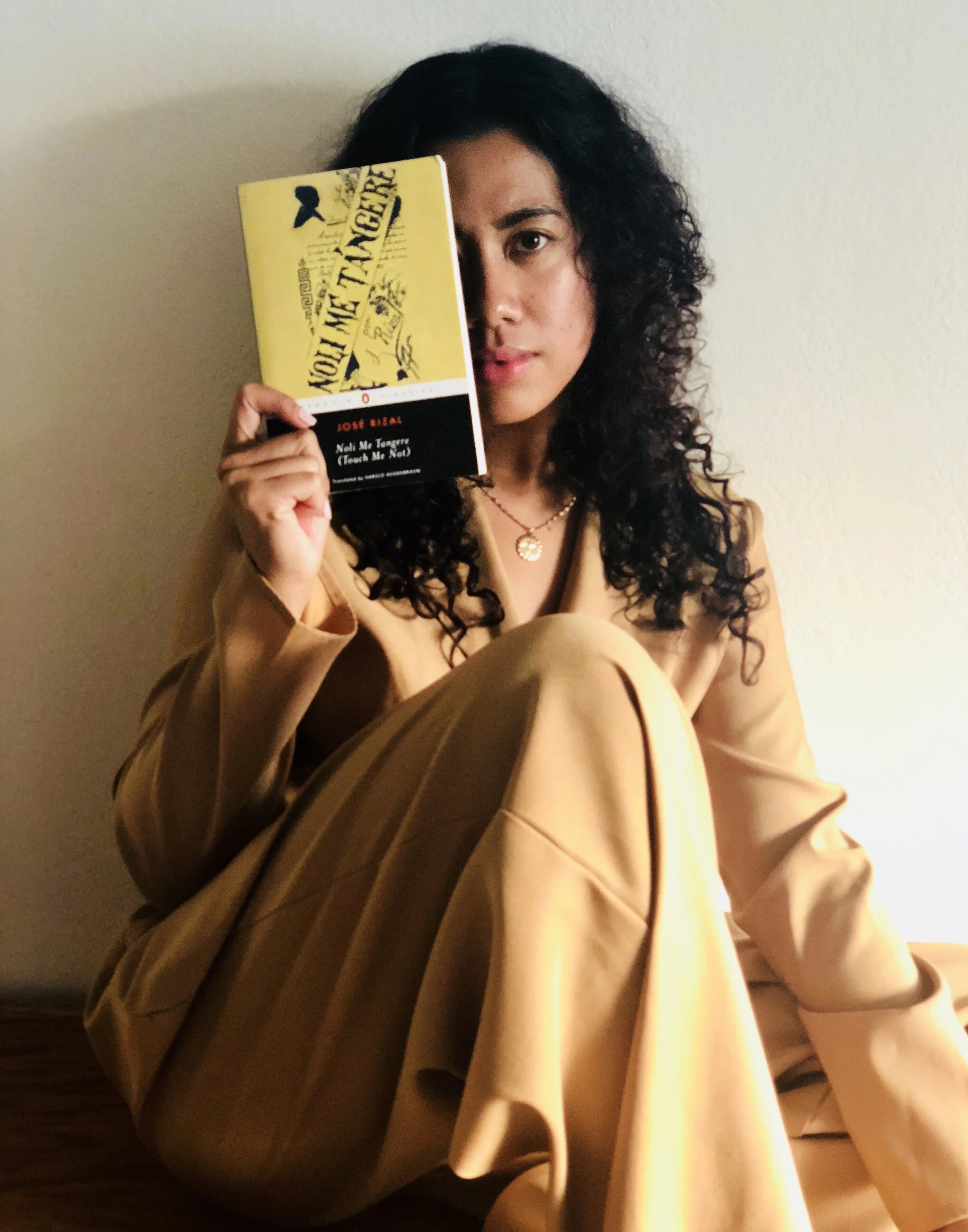

Illustration by Eduardo Daza Taylor IV for Hella Pinay

Many Asian Americans are reeling amid the recent swell of violence against our communities. We grieved for the six Asian women killed in the Atlanta-area spa shootings in March and the four members of the Sikh community killed in a shooting at an FedEx plant in Indianapolis a month later. We erupted into outrage over video footage of an assailant punching and kicking Vilma Kari in New York City, rendered all the more horrifying by a security guard closing the door after witnessing the scene from an apartment building lobby. It marked one of the latest in a string of attacks on our elders, which made us fear that our parents and grandparents could be next.

Asian American solidarity is more important now than ever. The power of the Asian American political identity lies in its potential as an organizing tool, especially in moments of intensified discrimination, as researcher, educator, and consultant Bianca Mabute-Louie explained on Instagram. Yet she also noted that it’s not without limitations. While the U.S. Census definition of “Asian” technically includes people from more than 20 subgroups, many hold a narrow view of who counts as Asian, and who doesn’t.

The South Asians, Southeast Asians, and Filipinxs I interviewed acknowledged a tendency in the U.S. to understand “Asian” to mean only “East Asian.” They pointed to a pervasive belief that Brown Asians aren’t “real Asians,” as well as a tacit hierarchy that positions them below East Asians — both of which undermine solidarity among our communities. Yet victims of anti-Asian violence have included Brown Asians, too. We need to show up for all Asian Americans.

In February, Kevin Nadal, a professor of psychology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and The Graduate Center of the City University of New York, tweeted about the omission of Brown Asians — South Asians, Southeast Asians, and Filipinxs — from a thread chronicling anti-Asian violence and xenophobia throughout history. “Dear East Asians, when you present Asian American History can you PLEASE make intentional efforts to include #BrownAsians?” he wrote.

Nadal clarifies that pointing out the erasure of Brown Asians doesn’t mean he’s anti-East Asian. “I’m not saying we shouldn’t care about East Asian elders that are being attacked. I think we need to care about everybody,” he says. “We need to care about all Asian Americans.” We need to be as outraged about Filipinx American Angelo Quinto’s death at the hands of police, the deportation of Southeast Asian refugees, and the attacks on South Asians post-9/11 — like the six members of the Sikh community killed in the Oak Creek Massacre in 2012 — as we are about the violence against our elders. Yet these incidents haven’t been as widely labeled as anti-Asian violence, or gained as much traction in the pan-Asian American community.

We’re still in the thick of the latest wave of violence, Nadal notes, making it hard to draw clear comparisons among the atrocities recently committed against members of various Asian diaspora communities. But generally speaking, the attacks on South Asian drivers — such as Subhakar Khadka, an Uber driver and Nepali immigrant, assaulted and coughed on in San Francisco, and Mohammad Anwar, an Uber Eats driver and Pakistani immigrant killed in a carjacking in Washington, D.C. — don’t “fit the same mold as these other attacks,” he says. The attack against Kari in New York City does, however, “so that incident is viewed as connected.”

Indeed, the nuances of Brown Asian subgroups matter, too. “Brown Asians consist of so many groups and they’re, by no means, all treated the same — especially because of phenotype and other factors,” Nadal explains. Our phenotype — very simply put, our physical appearance — largely influences our experiences with racism. South Asians tend not to be viewed as “Asian” because most of them don’t look East Asian. On the other hand, Southeast Asians often present similarly to East Asians, and for Filipinxs, it depends.

“Asian Americans in general just don’t perceive South Asians as Asian at all,” Nadal explains, while they view Southeast Asians and Filipinxs as “not Asian enough.”

“A minority within a minority”

Tasneem, a musician, artist, and activist who splits their time between Los Angeles and Toronto, and has Black and Gujarati Indian ancestry, didn’t see themselves as Asian until later in life. “In my mind, Asians were East Asians until I reached college, maybe even in the past 10 to 15 years,” they tell me. “I feel like I came up not thinking South Asians were Asian.”

TinTin V, a queer Lao American singer/songwriter, independent video game programmer, and community member of Laos Angeles, has no qualms with identifying as Asian American, but prefers to identify as Lao American. “I think that opens the conversation more,” he explains. People tend to have fewer preconceptions of Lao American identity than they do of Asian American identity.

As a Filipinx and Indonesian American, I’ve occasionally heard some variation of “Filipinxs aren’t real Asians” from Asians and non-Asians alike. I remember watching a person-on-the-street style Fung Bros YouTube video years ago that asked folx whether Filipinxs are Asian, a question that others on the Internet, including Filipinxs, have grappled with, as well.

It’s complicated. While some East Asians don’t see us as Asian, some of us don’t see ourselves as Asian, either. In the past, I’d sometimes distance myself from the “Asian American” category, because it didn’t seem to have room for me. To this day, like TinTin V, I feel more comfortable identifying as Filipinx and Indonesian because the way many perceive “Asian American” — as East Asian — doesn’t fit my experience. (Although my father is mostly ethnically Chinese, he’s from Indonesia and, for what I imagine to be complex reasons, identifies as Indonesian, not Chinese.)

A similar rationale seems to underlie the practice of Filipinxs claiming the Pacific Islander identity, which Anthony Ocampo, an associate professor of sociology at Cal Poly Pomona, discussed in a recent interview with One Down. In his research, Ocampo found that most Filipinxs who’d chosen to identify as Pacific Islander did so “not because they had a very strong connection to some larger Pacific Islander social movement, but... as an act of resistance against the Asian category,” in order to distinguish themselves from other Asians.

I’ve encountered Filipinxs who described themselves as Pacific Islander, probably stemming at least partly from our communities’ shared ancestry. Ocampo told One Down that he also knows many Filipinxs who’d identify as such, but may not be aware of issues important to the Pacific Islander community, such as the erasure of their Indigenous cultures and the ongoing colonization of their lands. “I think in some ways I understand why Filipinos picked Pacific Islander identity, but I also think that it can be problematic,” he said.

In Asian and non-Asian spaces alike, my Indonesian identity often goes overlooked, as well, especially given that Indonesians number only 129,329, or about 0.5 percent of the Asian American population, according to census data. I can relate to TinTin V’s experience of being the only member of his community in attendance at Asian American events, although he notes that maybe others were present, and they just weren’t aware of their shared identity. Per census data, people of Lao descent account for around one percent of the Asian American population.

An Indigenous identity can create an added layer to the marginalization Brown Asians already experience. “In Asian American spaces in college, my identity and experiences felt minimized relative to East Asians, who made up the majority of the already-small Asian American population,” says H’Abigail Mlo, a storyteller and cultural organizer in Philadelphia whose family is Montagnard, indigenous to Vietnam.

Even among Asian Americans, she wasn’t safe from the “What are you?” question. “When I would answer, I was sometimes met with confusion, as though I didn’t say what they wanted or expected, as though, somehow, they couldn’t believe a person could be Asian and Indigenous,” says Mlo, whose parents’ tribes are Jarai and Rhade. The non-Asians who did perceive her as Asian assumed she was East Asian, and projected East Asian stereotypes onto her — assuming she was good at STEM, for instance.

“As far as the Southeast Asian ethnic minority, we do tend to get erased in the larger narrative of Asian American identity,” says H’Rina DeTroy, a Montagnard American writer and instructor making radically intentional spaces for Montagnard/Indigenous and other members of the Southeast Asian diaspora. Her mother’s tribe is Jarai, and her father is white.“I feel like there has been conscious awareness to expand the umbrella and to make… folks in my community feel more welcome, but there’s definitely a lot of space for there to be way more work.”

Tasneem’s Black identity has also magnified the marginalization they’ve experienced in the Asian community. “When I was first starting out in music, I felt like I wasn’t accepted by the Black community because I wasn’t Black enough, and I wasn’t accepted by the South Asian or Indian community, or the Asian community, because I wasn’t Asian enough,” they say. Their Muslim, queer, and nonbinary identities further marginalize them. They also recall not feeling entirely welcomed by the Indian student organization in college because their parents aren’t from India, but from the diaspora — specifically Uganda and Kenya.

Although multiracial Brown Asian Americans are overlooked for many reasons other than the reasons their monoracial counterparts are, “there is a similarity to why they’re being erased,” Nadal says. “There is a group that sets those norms, who set the culture of who gets to identify as Asian American.” For those who are Black and Asian, “there’s the anti-Blackness component. So it’s not just that you’re mixed race, but you’re also Black,” which introduces colorism and biased beauty standards that influence their experiences within Asian American communities.

This isn’t to say that East Asians don’t experience erasure. They absolutely do. The model minority and perpetual foreigner stereotypes invisibilize them, too. But that erasure can be exacerbated for us Brown Asians, who are overlooked members of an already overlooked group.

“I think the mainstream American consciousness is still grappling with what Asian American identity is, number one, and still trying to wrap their heads around the fact that there is this model minority stereotype, which seems to contradict the fact that poverty, low high school graduation rates, crime, and incarceration are also realities in certain Asian American communities,” DeTroy says. “What seems to almost complicate that discussion or awareness is to then invite in this idea that there is a minority within a minority. Violence targeted at Asian Americans seems to reveal a reality that might also contradict the model minority myth — or complicate it.”

How we got here

As limited as the “Asian American” identity is in its ability to capture the diversity and complexity of the communities it encompasses, we can leverage it for political capital. That’s why it emerged in the first place, as Nadal describes in his article, “The Brown Asian American Movement: Advocating for South Asian, Southeast Asian, and Filipino American Communities,” published in Asian American Policy Review.

Most Asian Americans identified with their ethnic group until the 1960s, Nadal tells me, when Chinese, Japanese and Filipinx American activists on the West Coast began working together to advocate for issues related to ethnic studies and student organizing. They called themselves “Asian American” “because they found there could be potentially more power in a collective.”

Eventually, “Chinese and Japanese Americans started to be the voice of what ‘Asian American’ meant,” Nadal says. In response to the Black Power Movement and the Brown Power Movement, they suggested calling their movement the Yellow Power Movement.

“Filipinxs at the time didn’t identify with the color yellow and so as a result of that, they started to notice that this community may or may not be for them, may not necessarily represent their voices,” Nadal says. In the 1970s, Filipinxs and Pacific Islanders were already forming their own caucuses with Asian American subgroups, known as Brown Asian caucuses, so they could discuss the issues they faced, which were distinct from those of other Asian American groups.

While Chinese and Japanese American activist groups didn’t individually outnumber Filipinx activist groups, together they did, Nadal explains. After the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 abolished immigration quotas based on country of origin, the U.S. saw a stream of Korean immigrants, which further skewed the Asian American population toward East Asians.

More Brown Asians immigrated to the U.S., but various factors complicated the picture. South Asians arrived in larger numbers after 1965, Nadal says (although he points out in “The Brown Asian American Movement” that they first landed in the U.S. in the late 1800s). Yet in 1970, the census classified Indian Americans as white, before creating an “Asian Indian” category in 1980. Southeast Asians — such as Hmong, Lao, Cambodian and Vietnamese Americans — came mostly as refugees in the 1970s and 1980s, but their role in activism differed from that of Asian Americans who’d been in the U.S. longer.

Some have taken to social media to recognize Middle Eastern folx as Asian, too, specifically West Asian. “Many may want to identify as part of the umbrella because they want some recognition, since they’re more typically excluded altogether in any racial dialogue and classified in the census as white,” he says. At the same time, he’s noticed the term MENA, short for Middle Eastern or North African, emerge in his own field of psychology.

All of this is to say that race is a hazy concept, and some people with Middle Eastern ancestry might identify as MENA, others as West Asian, and others as a part of a separate group entirely, Nadal explains. If someone identifies as both West Asian and Brown, he notes, then they’re Brown Asians, too.

Like other racial categories, the definition of “Brown Asian” has shifted over time and may very well continue to do so. At first, Nadal says, it included Filipinxs but has since broadened to encompass South Asians and Southeast Asians, as well. He expects the recognition of Middle Eastern folx as Asian to take a while to catch on, in the same way that Filipinxs and South Asians might not have intuitively identified as Asian, at least initially.

“It goes back again to the origins of Asian American movement in general,” Nadal says. “Will a group get more recognition as part of a larger group and potentially be marginalized, or less recognition as a smaller group and not have power in numbers?” In other words, when you consider the origins of “Asian American” as a political strategy, its use to refer to such a vast panoply of communities — and the invisibilization of certain communities — makes sense.

Nadal likens the broader Asian American community to an organization, where “the first few people set the tone of the organization. As more people come, things might be different, but that core has been set.” Even though Brown Asians now outnumber East Asians — making up around 60 percent of the Asian population in the U.S., as Nadal noted in “The Brown Asian American Movement” — “the tone of what people know to be Asian, how Asian American leadership is run, and who sets the agenda have already been set, so that then affects the whole dynamic of the community.”

Fancy Asians and Jungle Asians

While the Philippines is in Southeast Asia, Nadal lists Filpinxs separately from Southeast Asians for a number of reasons, such as their presence in the U.S. decades before the arrival of Southeast Asians. By then, Filipinx Americans had already developed a distinct identity. Our religion, language, and colonial history also differs from those of Southeast Asians, and our sociocultural and educational experiences lie somewhere between those of Southeast Asians and East Asians.

Both of us, though, are what Chinese and Vietnamese American comedian Ali Wong would consider “jungle Asians.” “The fancy Asians are the Chinese, the Japanese. They get to do fancy things like host Olympics. Jungle Asians host diseases,” she says in her Netflix special Baby Cobra, giving comedic voice to an unspoken hierarchy among Asians, which Nadal attributes at least partly to racial hierarchies and colorism that deems light skin superior to dark skin. Brown Asians, as their name suggests, tend to have darker skin than East Asians.

We can see this hierarchy in data disaggregated by subgroup, which shows wider wage gaps for Brown Asian women. Although Taiwanese women out-earned white men by an average of 21 cents from 2015 to 2019, per the Center for American Progress, Cambodian women earned 40 cents less than white men during that time period. Nepali women earned 46 cents less.

And contrary to Students for Fair Admissions’ claim that Harvard’s race-conscious admissions policies disadvantage Asian Americans, Nadal notes that Southeast Asian and Filipinx Americans actually benefit from affirmative action. Edward Blum, the founder of the conservative group — which filed a lawsuit against Harvard in 2014 — culled support from affluent, highly-educated Chinese Americans in regions like the San Francisco Bay Area, the Washington Post reported.

That said, it’s important to note that East Asians struggle socioeconomically, too. For instance, the poverty rate in Manhattan’s Lower East Side/Chinatown was 30 percent in 2018, according to the NYU Furman Center, versus 17.3 percent in New York City as a whole. And a recent report by Asian Americans Advancing Justice - Los Angeles and AARP found that among people over 65 living in Los Angeles County, Koreans (along with Cambodians) are more likely to live below the poverty line than any other racial group.

Yet for all its lack of nuance, the hierarchy still stands, and microaggressions have reminded me of my place in it. Years ago, a former Chinese American colleague commented that an incoming Filipinx American colleague “looked like a thug.” Another, also Chinese American, told me I was “Filipino, but the educated kind.” I don’t remember how I responded. Maybe his words so stunned me that I couldn’t muster my own.

Indeed, Nadal points out in “The Brown Asian American Movement” that Brown Asians encounter not only microaggressions commonly associated with Asian Americans, such as those that play into the model minority myth, but others, as well. Southeast Asians and Filipinxs are often stereotyped as gangsters or criminals, South Asians as terrorists.

So while the term “Asian American” can be politically useful, it can also obscure the challenges certain communities face. “For us [Brown Asians], it’s not all about representation in the media,” says Kalaya’an Mendoza, an activist and co-founder of Across Frontlines, who is Filipinx American. “For many of us, it’s about fighting the ICE raids that are happening in our communities, fighting unemployment and displacement, fighting against the trauma of the U.S. military-industrial complex in our homelands.”

And again, the struggles of those with Indigenous identities are doubly invisibilized.. Besides colonialism and imperialism under Vietnam, France, and the U.S., “we continue to experience ethnic cleansing in Vietnam and deportation in the United States,” Mlo tells me of her Montagnard community. “My diasporic community here in the United States has historically been uncounted…. Many Asian Americans are privileged, without even knowing it, to not have to worry about their histories being erased or their cultures dying.”

Creating space for all of us

East Asians and non-Asian allies can and should take steps in their personal lives to include all Asians. For starters, they can speak with intentionality, Nadal says. When they label something as “Asian,” they need to ask themselves if they truly mean all Asians, or just East Asians. Also, whenever they attend an Asian American panel, they need to scrutinize who has a seat at the table. Nadal notes that on Clubhouse, most of those leading the conversations about anti-Asian violence have been East Asian men. “Why isn’t there intentionality for there to be more women, or more South Asians, Southeast Asians, people with different sexual orientations and gender identities?” he wonders.

Lastly, East Asians and non-Asian allies need to challenge their biases, and think about how they affect what they consider important, who they advocate for, and what they relate to most. This knowledge can help them ensure that they’re speaking out in support of everyone. The East Asians who retweeted my call for sources for this story — specifically, South and Southeast Asians who felt marginalized in the Asian American community — indicates that at least some recognize that this is an issue, which I see as an encouraging sign.

Although some might criticize efforts to highlight the marginalization of Brown Asians as divisive, Nadal says people have always responded in this way to those who call out power dynamics, “instead of honoring that their lived experiences are actually based on truth.” It’s not uncommon to hear white folx say the same about BIPOC who call out racism, or gay and lesbian folx say the same about transgender folx who call out transphobia. “The list goes on.”

What’s divisive is a pattern of spotlighting some communities while erasing others.

“These other groups who are not considered and who are not mentioned can, will, and have resented the fact that they are invisible,” DeTroy says. “It means that we can’t all work together strategically. It affects all of us.” We’re strongest when we can all stand in solidarity with each other.

Melissa Pandika

INSTAGRAM - WEBSITE

Melissa Pandika (she/her) writes about wellness, race, and identity. Her words have appeared in The Cut, VICE, Mic, and many other places. She lives in the Bay Area and is at work on a memoir.