OVERFLOW // Unpublished Excerpts from Nervous: Essays on Heritage and Healing

Hella Pinay is excited to print a previously unpublished excerpt from Jen Soriano's debut book NERVOUS: Essays on Heritage and Healing.

Jen's book is an epic ride through Philippine history, personal history, the silenced history of American colonization, and exciting developments in the social neuroscience of trauma. Their work is a testament to the power of facing history and flowing toward embodied connection. They describe it as a love letter to bodies survived, and a vision of freedom through interdependence.

Writers know it takes reams of drafts to get to a final piece. These excerpts come from the first full draft of what became NERVOUS, and Hella Pinay is happy to bring them to you from the cutting room floor.

OVERFLOW

Unpublished Excerpts from Nervous: Essays on Heritage and Healing

By Jen Soriano

Prologue

We are a society of nerves. muscle. sinew:

of illusory impermeability and T-bone steaks.

We are a civilization of flint and steel:

of Glocks and bayonets, bolos and

drones AR-15s. Knees.

And although armored we are tender

We

Americans may be

(may we be)

trembling we have woven bootstraps from streams

anchored scaffolding in silt

We may feel

(may we feel)

that this is an increasingly nervous time.

~

A body in time, I am the impulse of circuits seeking completion

of watersheds longing

for a steward to return.

May we be a confluence of rivers:

an estuary dreaming

a society iridescent and sourced

a civilization with the multivalence of water

with the potential

to be dredged

and undammed

I will sing

of being waterborne

adapted to the current

permeated by the past

We will sing

of becoming

tender and blinding

all the nacred pearls unshelled

tributary: orienting

Yet another night of wrestling with sleep. Or more accurately, wrestling with the phantoms that want to keep me awake. Nights like this I am ruled by my amygdala. I have done enough therapy to have the higher regions of my brain greased and ticking for most of my working hours. But when everyone else goes to sleep it’s just me and my reptile brain. We are not exactly fighting. We are more like chillin’ at opposite sides of a lounge, pretending to not know each other and yet watching each other’s moves out of the corner of our eyes.

I realize my eyes are fixed on the phantom in my lizard mind. This is the past, not the present. This doesn’t have to be my reality.

And so I begin to orient. This means I begin to move my eyes around the room and take note of what’s around me. Crumpled white comforter, Juan sleeping soundly on his stomach, a slice of light from the streetlamp cutting through the bent window blinds. My eyes rest on the rectangle of light that shines onto the brown cork floor. I notice how soft the bed is beneath me and feel my body become more open to sleep.

Orienting is something my somatic therapist recently taught me to do. It’s not just a calming exercise, it’s a neural retraining exercise. Our eyes are a direct connection to our central nervous systems; the optic nerve is directly connected to the vagus nerve, and orienting actually helps stimulate the vagal brake that calms our stress response.

The voluntary movement of our eyes activates neocortex circuits that inhibit amygdala-based reflexes that lead us to orient narrowly in order to pinpoint threat.

Choosing to move our eyes and allowing them to rest where they want to linger activates broader orientation circuits that allow us instead to observe what’s around us with a wider-angle lens. It allows us not to ignore threat and filter out danger, but instead to welcome in the aspects around us that actually are safe.

I hear sirens then see them move past our building. I see people walking on the sidewalk and notice they are not coming for me. I tune into the whirring of the traffic, Juan’s rhythmic breathing, and small objects of everyday life that surround us—the scattered pile of earplugs next to my phone, the crumpled tissues that missed the garbage can, the piles of paperwork with unused appliance manuals hiding overdue bills. Noticing these ordinary things help remind by nervous system that I can surrender my hyper-vigilance; fight or flight is not necessary right now.

I get out of bed to go to the kitchen, find my medication, and take it to help me fall fall fall to rest. While I wait for the medication to kick in, I open the door to Little T’s room and what I see helps bring me closer to rest. He is sleeping with his moon face pressed against a giraffe. He is not afraid of his stuffed animals like I once was. He seems to have inherited his father’s trust in his own body and the wisdom of circadian rhythms, he seems to have inherited other ancestral wiring for deep and peaceful sleep.

tributary: reflections

I have come to understand that what I carry with me is not my own failings, but the traumas of my ancestors who had survived nearly 400 years of violent colonization. I have come to understand that the unspoken stories of my ancestors live on in my body, and that I must accept these stories as broken words, splinters and shrapnel, not as complete artifacts with full characters and story arcs intact.

I must also accept that there are many who don’t want these stories to be told. Judith Herman writes: “The conflict between the will to deny horrible events and the will to proclaim them aloud is the central dialectic of psychological trauma.” Many people say the past is past, move on. Why do you want to play the victim? I’m learning that this is a coping mechanism disguised as strength. Some of us, like my parents and grandparents, had to move on to survive. There was no time to lick wounds. For others of us, it feels easier to bury or blame than to do the hard work to heal.

But trauma is there whether we decide to face it or not. You can drive it below the surface but it will still be there, polluting the depths. Herman writes, “Folk wisdom is filled with ghosts who refuse to rest in their graves until their stories are told.” Facing these ghosts is not easy. Homi Bhaba writes: “Remembering is never a quiet act of introspection or retrospection. It is a painful re-membering, a putting together of the dismembered past to make sense of the trauma of the present.”

It’s not easy, but the ghosts can be very insistent. Those that haunt me have found the quick and myelinated access to my nerves. They pull on these circuits, triggering axes and cascades and disrupted feedback loops that at times cause bewildering pain. But this pulling also grounds me, tethers me to a soulful identity that impels me to put fragments of stories, images, scents, feelings to words.

Here is something my ancestors want me to say: the effects of 400 years of colonization are not washed away overnight, or in one generation, or even two or even three.

Something else: it is not our fault.

And more: our fight for survival is our strength, but so is our joy—our rooted joy.

And of course: there will always be suffering and pain, so never forget to laugh and dance and sing.

To that I would add: And eat mangoes. Yellow or green, with or without bagoong. Be tender, with yourself and with others. Hug the ones you love.

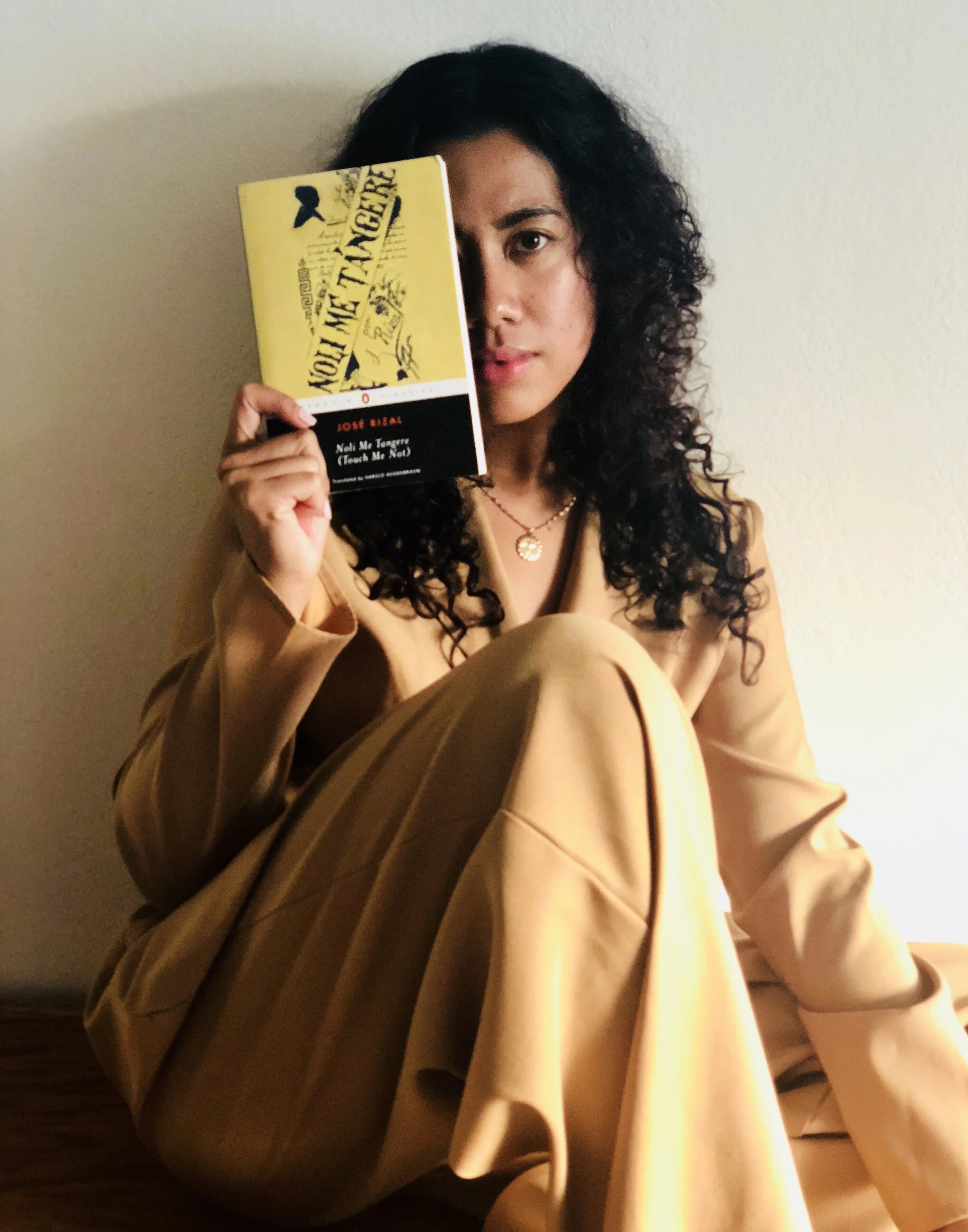

thumbnail image credit: Sherisa DeGroot, Raising Mothers

Photo: Naomi Ishisaka

Jen Soriano

INSTAGRAM | tiktok | WEBSITE

Jen Soriano (she~they) is a Filipinx writer and movement builder who has long worked at the intersection of grassroots organizing, narrative strategy, and art-driven social change. Jen is the author of Nervous: Essays on Heritage and Healing, which was recognized by TIME, GLAMOUR, The Atlantic, Poets&Writers, and other outlets as a notable book of 2023. Jen is author of the chapbook “Making the Tongue Dry,” and co-editor of Closer to Liberation: A Pina/xy Activist Anthology, and their work has won the International Literary Award for Creative Nonfiction and the Fugue Prose Prize, as well as fellowships from Hugo House, Vermont Studio Center, Artist Trust, and the Jack Jones Literary Arts Retreat. They received a BA in History and Science from Harvard and an MFA in fiction and nonfiction from the Rainier Writing Workshop. Jen is also a co-founder and former board chair of the cultural democracy institutions, MediaJustice and ReFrame, and is a leader in the field of narrative justice. Originally from a landlocked part of the Chicago area, Jen now lives with her family in Seattle, near the Duwamish River and the Salish Sea.